We posed the following statement to a group of emerging artists and asked them to respond creatively.

STATEMENT:

Hosting the World Cup in 2006 and then making it into the final was a fine moment for Germany. It was the first time many people displayed German flags on their cars. Some have even said that at last they felt the world was no longer judging them, but accepting and admiring them. In 2006, the whole world came to Germany and Germany exceeded expectations.

The energy and the spirit evoked in the country coming together to celebrate this time was a catalyst for an ever growing feeling of pride / excitement amongst Germans, young and old – nothing to do with nationalism or patriotism.

The new Germany is unencumbered by a difficult past. The wars are now last century, and they are not the burden of today’s generation. The new Germany is guilt free, young and open to a bright future. Germany’s future is one to be reinvented by its young people.

Friday 12 October 2007

DIE JUGEND

Die Jugend

“Denk ich an Deutschland in der Nacht, ward ich um den Schlaf gebracht”

Heinrich Heine

(Thinking of Germany at night; just puts all thought of sleep to flight)

Heinrich Heine

(Thinking of Germany at night; just puts all thought of sleep to flight)

To many Germans, the quote above encapsulates awkward contemplation. Wrangling over the vergangenheit and the present is so common it could be a national sport. But to the planeloads of clubbers flocking through Berlin’s airports, those sleepless nights have an altogether different meaning. To them, the capital is a bohemian playground where anything might, and does, happen.

As unique as the myth of Berlin may seem, and as airbrushed as it may be, it does have some resonance for the country at large. Division has been replaced by unity – geographically, at least – and the government has finally clawed itself back into the black. Optimism aside, Germany remains a complex and fragmented nation, with multiple pockets of opportunity and impoverishment. Racial tensions show no signs of evaporating, with sobering assaults never far from the headlines. Youth stand between anticipation and fear; opinions and plans tempered by a wider consciousness uncommon to most of their European peers.

Yet the future of Germany’s people is bright precisely because of (not despite) their dark collective past. The weight of guilt is a constant check on potential excesses, and ensures an underlying freedom more vital than ever. Introspection, openness and a desire for reconciliation have transformed Germany from headstrong aggressor to a bastion of sanity and civility. The majority of its youth are blessed with these virtues, and are all the more stable for them.

Teutonic jingoism has, by and large, been replaced by maturity. It is a trait visible here in Germany’s children – irrespective of background.

CULT-GEIST: Personal Optimism

KALTWASSERSPRUNG

We took a dual approach to this idea. One of us being an American, where pride is a value that is learnt at an early age. Another with a German heritage that has been taught to reflect on their past actions and not to be too boastful. This approach has given us a good insight into this topic. It has allowed us to see this from two sides. To touch this topic with a sense of opitimism, but also a sense of skepticism.

Today in Germany the word “Stolz” (pride) still has a negative connotation attached to it. It still has a connection to the past ideals of the fascists of the third reich and what they promoted in their national socialist values. Even by definition pride in Germany is still connotated with arrogance and self-absorbance. Only when one achieves something solely by himself you can consider yourself proud: 'I am so proud I gave up smoking'. Therefore using the word pride is still widely considered morally doubtful, at least not a matter of good taste.

Optimism is a new and present feeling in some of the youth today. But there is still a reluctance to not be too overly optimistic. Fearing the unknown in the youth is the general feeling that spans the full spectrum of beliefs.

We are not making any statement whether it is good or bad to use the word pride. Neither do we say if there actually is a new sense of optimism. But we have found out that there is an insecurity regarding the two terms. Germans do feel a self confidence but they might be unsure of how to express that in appropriate ways.

Ins kalte wasser springen, means, to jumping into the unknown.

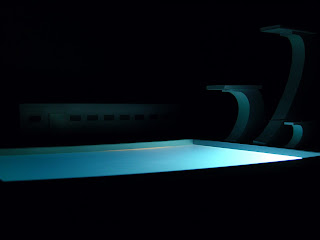

We see this as one might see the future is bright, refreshing, opportunities are around the corner if one just takes that first step. To challenge yourself to step off the spring board into the cold water. Blueish water in the pool connects to the metaphor which symbolizes the calming refreshing attributes of this giant steps in the many phases of the growth in this reunified country. This all gives a feeling of the potential for growth in the people of Germany.

The anxious atmosphere of the picture represents the need to reflect on the dark past. The pool promises that jumping into the water can be refreshing, revitalizing, washing off the past to build strength in the people and the community. This dark feel to the image is to still remind someone that there is still uncertainty and that difficult times are still ahead. But to remember that one just has to take those first steps to know that there is a chance to grow. To make a future out of a past that is still reminded to you everyday.

NOTES:

(from the artists own notes)

The use of water as a metaphor for washing off the past, revival and renewal.

The greenish / blueish tint on the springboards gives a feeling of hope to the German people.

CULT-GEIST: Jumping Into The Unknown

DENKMAL (a short clip for C-G)

by Alison Boland

After studying abroad in Berlin in 2005, I devoted my studies to learning as much about the city as possible. My primary focus was on the architectural and memorial landscape of the city and its relationship to a complex discourse on the definition of German national identity. I found the subject interesting because of the intense insecurity Germans expressed about their fascist past as well as their future standing in the European Union and the world. For me, Germany's questioning self-image stood in welcomed contrast to my own experience of the United States' blind optimism about its role in global affairs.

In the summer of 2006 I returned to Berlin to make a documentary about the city's memorial landscape. I intended to definitively capture the current state of the symbolic landscape on film and to predict where the German identity debate was heading in the 21st century.

I arrived just as the city was gearing up to host the 2006 FIFA World

Cup. What I saw was not something that I expected to see: widespread German patriotism.

For me, this opened up a crack in the academic discourse. If this was a nation defined by self-doubt, how could so many of its citizens be patriotic? Were they reacting to the stifling insecurity that had described them in years past? Was the youngest generation of Germans trying to redefine its homeland as a place to be proud of? Was it okay for Germans to want to be German again?

Many people that I talked to said that the flag-waving was about the celebration of the event more than the statement about nationalism. But if they were waving German flags, how could they not be making a statement about national identity? It seemed so complicated, and some people on TV were talking about how wrong it was that there should be a resurgence of German nationalism. They said that it reinforced neo-Nazi ideals. But the flag-waving continued, despite these accusations. The general public didn't seem to care.

Did the people waving flags on the street know more than I did? Or was I just thinking about things too hard. Maybe they were cheering for Germany, or maybe they were just cheering for a soccer team.

These questions about patriotism hit close to home for me and answering them immediately became more important to me than mapping the urban memorial landscape.

Denkmal is a movie about Amy, an American girl who has come to Berlin to make a movie about monuments and to learn more about the city. Disenchanted with her own country, she wishes she was a real-Berliner. The movie follows Amy's semi-romantic encounter with Jonas, a native East-Berliner. As their story unfolds, we also witness Amy's parallel struggle to reconcile her academic experience of Berlin with that of the city she explores with Jonas.

Monuments act as the primary metaphor in the film. In relation to nationality, monuments signify an official definition, engraved into stone and unable to change as the mindset of the people around it change. In a similar way, when Amy meets Jonas, she already has an idea of what Germans his age are like. As a result, she misses the opportunity to really get to know him. Therefore, just as a monument cannot eternally symbolize the opinion of an entire nation of people, neither can a single person be a monument to a generation.

I SEE SOMETHING YOU DON'T SEE

by Bella Lieberberg

I created a series of portraits that illustrate tattooed people, whose bodies have been morphed / transformed into story books, telling us their individual life stories.

We are not talking about some randomly chosen common tattoos like the infamous “sailor” or “I heart mum”, but tattoos that allow us to intimately glimpse into their souls, identities, character and attitude towards life. Germany even though being traditionally characterized as uptight, conservative, with a love for following “law & order” is witnessing the birth of a new generation of kids who are fed up with these clichés which best described their grandparents.

Somebody who tattoos their necks sends a strong signal to the society he is living in. “Fuck off”

I don’t want to work in a bank and I don’t want to live a conventional life. Their tattoos often have deeply emotional significance to them as they told me while shooting. The body is converted into a piece of art and in that sense illustrates their desire to be different, their cry for individuality in a society of sheep. It is still a sign of rebellion against a hegemonic society with its dominant ideologies – kind of brave as it visually signifies that you don’t want to belong to the rest – that youre anti-identifying. They are eternal pictures that treasure memories forever – images and stories that they don’t won’t to forget and proud to show off.

I deliberately let them choose their own background with the chalk board to highlight their individual tattoo stories/characters. Hence the observer not only observes but explores. It allows diving into their life stories and their narrative for a brief moment. I also strongly believe that no other medium provides such a strong and intimate closure as the tattoo to the tattooed person. Tatoos as the lightbringer for a more liberal and tolerable German future.

CULT-GEIST: Spirit of Individuality

I created a series of portraits that illustrate tattooed people, whose bodies have been morphed / transformed into story books, telling us their individual life stories.

We are not talking about some randomly chosen common tattoos like the infamous “sailor” or “I heart mum”, but tattoos that allow us to intimately glimpse into their souls, identities, character and attitude towards life. Germany even though being traditionally characterized as uptight, conservative, with a love for following “law & order” is witnessing the birth of a new generation of kids who are fed up with these clichés which best described their grandparents.

Somebody who tattoos their necks sends a strong signal to the society he is living in. “Fuck off”

I don’t want to work in a bank and I don’t want to live a conventional life. Their tattoos often have deeply emotional significance to them as they told me while shooting. The body is converted into a piece of art and in that sense illustrates their desire to be different, their cry for individuality in a society of sheep. It is still a sign of rebellion against a hegemonic society with its dominant ideologies – kind of brave as it visually signifies that you don’t want to belong to the rest – that youre anti-identifying. They are eternal pictures that treasure memories forever – images and stories that they don’t won’t to forget and proud to show off.

I deliberately let them choose their own background with the chalk board to highlight their individual tattoo stories/characters. Hence the observer not only observes but explores. It allows diving into their life stories and their narrative for a brief moment. I also strongly believe that no other medium provides such a strong and intimate closure as the tattoo to the tattooed person. Tatoos as the lightbringer for a more liberal and tolerable German future.

CULT-GEIST: Spirit of Individuality

WIE FUEHLT MAN SICH ALS DEUTSCHE(R)?: HOW DOES IT FEEL BEING GERMAN?

by JUJU

The relationship a country has to its flag is a good indicator of the feeling towards its nationality. Just four years ago a young German band had posed for a photoshoot wearing the colours black-red-gold. It had caused an outcry and they were bashed by the feuilletons for promoting unreflected nationalism. So it was a shocking sight at first when during the world cup German flags appeared everywhere. But through this experience the flag has undergone a reappropriation and today it signifies the unitiy of the German people.

But how does it feel being German? Since I had lived abroad for many years and only recently returned to live in Berlin (which has nothing in common with the rest of Germany ...) the question of nationality is something I had to deal with all the time. In the UK being German defined me and made me a representative of an entire country. In Berlin I can be just myself again and it was fascinating to rediscover a country which had changed considerably during my absence. My feelings towards being German are very ambiguous.

My aim was to respond with an image which wasn't taking itself too serious. I wanted to create three characters expressing the different sentiments I have towards my nationality. Based on the colours of the German flag I created a sad, an angry and a happy sausage. I chose to use sausages on a plate to make visible how these different sentiment are equal and exist side by side. Only by reading the title the expressions of the sausages take on meaning. It is posed as a question because your nationality is something which can only be defined in relation to other nations.

As national identity exists within the realms of ideas and I didn't want to produce an object (like a framed print). Instead the illustration is supposed to be painted directly onto the wall. As such it becomes part of the room rather just being placed in it.

The relationship a country has to its flag is a good indicator of the feeling towards its nationality. Just four years ago a young German band had posed for a photoshoot wearing the colours black-red-gold. It had caused an outcry and they were bashed by the feuilletons for promoting unreflected nationalism. So it was a shocking sight at first when during the world cup German flags appeared everywhere. But through this experience the flag has undergone a reappropriation and today it signifies the unitiy of the German people.

But how does it feel being German? Since I had lived abroad for many years and only recently returned to live in Berlin (which has nothing in common with the rest of Germany ...) the question of nationality is something I had to deal with all the time. In the UK being German defined me and made me a representative of an entire country. In Berlin I can be just myself again and it was fascinating to rediscover a country which had changed considerably during my absence. My feelings towards being German are very ambiguous.

My aim was to respond with an image which wasn't taking itself too serious. I wanted to create three characters expressing the different sentiments I have towards my nationality. Based on the colours of the German flag I created a sad, an angry and a happy sausage. I chose to use sausages on a plate to make visible how these different sentiment are equal and exist side by side. Only by reading the title the expressions of the sausages take on meaning. It is posed as a question because your nationality is something which can only be defined in relation to other nations.

As national identity exists within the realms of ideas and I didn't want to produce an object (like a framed print). Instead the illustration is supposed to be painted directly onto the wall. As such it becomes part of the room rather just being placed in it.

MY PRIVATE LITTLE GERMANY

by Holger Von Krosigk

Benni (26)

Occupation: Consultalt

Outlook: likes Germany, loves Spain & France

Says: “I feel ashamed for my countrymen when I see them on holidays.”

Hates: the German flag

Britta (23)

Occupation: accountant

Can't imagine: living anywhere else than in Germany.

Outlook: very optimistic

Believes: that Germany is on a good path

Gerhard (53)

Occupation: Taxi driver

Outlook: has always been very skeptical

Loves: the German football team

Igor (61)

Occupation: picking up & returning bottles

Mother country: Romania

Outlook: it's hard without money, but easier in Germany than elsewhere

Says: “I don't know what to say...”

Isabell & Ömer (18 & 20)

Occupation: Apprentice & Barber

Outlook: Germany is a great place for young people.

Remember: The Football World Cup – “our best summer ever”

Joshua (12)

Occupation: schoolboy

Outlook: doesn't know what optimism is

Hates: long school days

Maria (57)

Occupation: owner of perfumery

Outlook: always optimistic - “that's my secret”

Loves: Cologne & her dogs

Deplores: the bad weather, “that's all!”

Patrick (26)

Occupation: skateboarder

Outlook: “I'm optimistic, I love Germany!”

Says: “most people lack political awareness...”

Hates: that Germans have no sense of fashion

Thomas (28)

Occupation: Graffiti sprayer

Outlook: doesn't think categories of “nations”

Loves: graffiti, BMX

Hates: boundaries

The success of the 2006 Football World Championship triggered a wave of appraisal of the "new" Germans. Not only was this troubled nation able to put on a smiling face, there was something distinctly new about the host. The image - and the self-image. The foreign visitors were thrilled by the warmth they felt in Fußball-Deutschland, and the international press was enthused by the fact that this new generation was finally able to show its colours again - proudly, yet peacefully.

Yet what exactly is a nation's self image? Where can I find it? In a museum? Is it locked up in some government-room or a statistic value worked out by a hundred scholars based on two years of research? Do those people you find on the street subscribe to such a thing? There's of course nothing more artificial and constructed than such a concept. Go out on the street and ask ten people - you'll get ten different answers. So I figured, why not ask them?

The basic assumption here is that such feelings of national scope are private experiences. Whether or not a person is optimistic depends on an infinite number of facts ranging from age, profession or origin to personality traits. The following photos should underline this very fact. The manner in which the people present themselves on the pictures shows what they think about their feelings towards their mother country. As a matter of fact, their feelings towards it reflect nothing more than their general outlook on life. This is no attempt to doubt general tendencies, but a reminder of the individual nature of "feelings".

NOTES:

(from the artist's notes)

Their body language reflects how they feel.

Benni (26)

Occupation: Consultalt

Outlook: likes Germany, loves Spain & France

Says: “I feel ashamed for my countrymen when I see them on holidays.”

Hates: the German flag

Britta (23)

Occupation: accountant

Can't imagine: living anywhere else than in Germany.

Outlook: very optimistic

Believes: that Germany is on a good path

Gerhard (53)

Occupation: Taxi driver

Outlook: has always been very skeptical

Loves: the German football team

Igor (61)

Occupation: picking up & returning bottles

Mother country: Romania

Outlook: it's hard without money, but easier in Germany than elsewhere

Says: “I don't know what to say...”

Isabell & Ömer (18 & 20)

Occupation: Apprentice & Barber

Outlook: Germany is a great place for young people.

Remember: The Football World Cup – “our best summer ever”

Joshua (12)

Occupation: schoolboy

Outlook: doesn't know what optimism is

Hates: long school days

Maria (57)

Occupation: owner of perfumery

Outlook: always optimistic - “that's my secret”

Loves: Cologne & her dogs

Deplores: the bad weather, “that's all!”

Patrick (26)

Occupation: skateboarder

Outlook: “I'm optimistic, I love Germany!”

Says: “most people lack political awareness...”

Hates: that Germans have no sense of fashion

Thomas (28)

Occupation: Graffiti sprayer

Outlook: doesn't think categories of “nations”

Loves: graffiti, BMX

Hates: boundaries

The success of the 2006 Football World Championship triggered a wave of appraisal of the "new" Germans. Not only was this troubled nation able to put on a smiling face, there was something distinctly new about the host. The image - and the self-image. The foreign visitors were thrilled by the warmth they felt in Fußball-Deutschland, and the international press was enthused by the fact that this new generation was finally able to show its colours again - proudly, yet peacefully.

Yet what exactly is a nation's self image? Where can I find it? In a museum? Is it locked up in some government-room or a statistic value worked out by a hundred scholars based on two years of research? Do those people you find on the street subscribe to such a thing? There's of course nothing more artificial and constructed than such a concept. Go out on the street and ask ten people - you'll get ten different answers. So I figured, why not ask them?

The basic assumption here is that such feelings of national scope are private experiences. Whether or not a person is optimistic depends on an infinite number of facts ranging from age, profession or origin to personality traits. The following photos should underline this very fact. The manner in which the people present themselves on the pictures shows what they think about their feelings towards their mother country. As a matter of fact, their feelings towards it reflect nothing more than their general outlook on life. This is no attempt to doubt general tendencies, but a reminder of the individual nature of "feelings".

NOTES:

(from the artist's notes)

Their body language reflects how they feel.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)